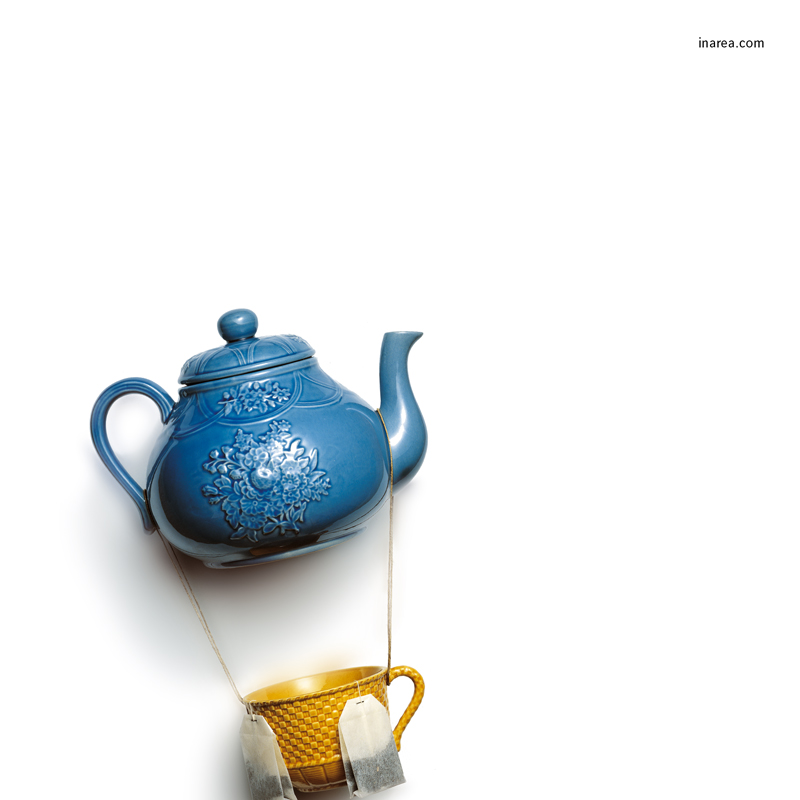

Rise and shine

“The silence of the place was dreadful”, is how Perrault describes the Prince’s impression when he arrives at the castle, shortly before breaking the spell which had kept Beauty asleep for one hundred years. We could do with a fairy tale, even after one week; a week during which, with a great deal of effort, we found ourselves having to climb down from the comet and resist our homes’ cosiness that kept slyly beckoning us back to bed. Indeed it would take a ruse to trick “Blue Monday”, a name that will be plastered all over the web today to remind us that this particular Monday is a bit more depressing than usual. In actual fact, the concept had been devised some time back as a publicity stunt by a travel agency; the latter claimed to have calculated the date based on a peculiar mathematical equation that summed together the cold and dismal weather conditions with having to go back to work. The formula was later dismissed as pseudoscience. In the original version of “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood” the fairy tale unexpectedly takes on nightmarish tones after the wake-up kiss: the Prince and Princess have to deal with an ogress mother-in-law-queen, protect their children from her and see to the running of a castle. A far cry from the “and they lived happily ever after” ending. But then we too need to rise and shine: washing away those Monday blues under the shower may help us make a fresh start.