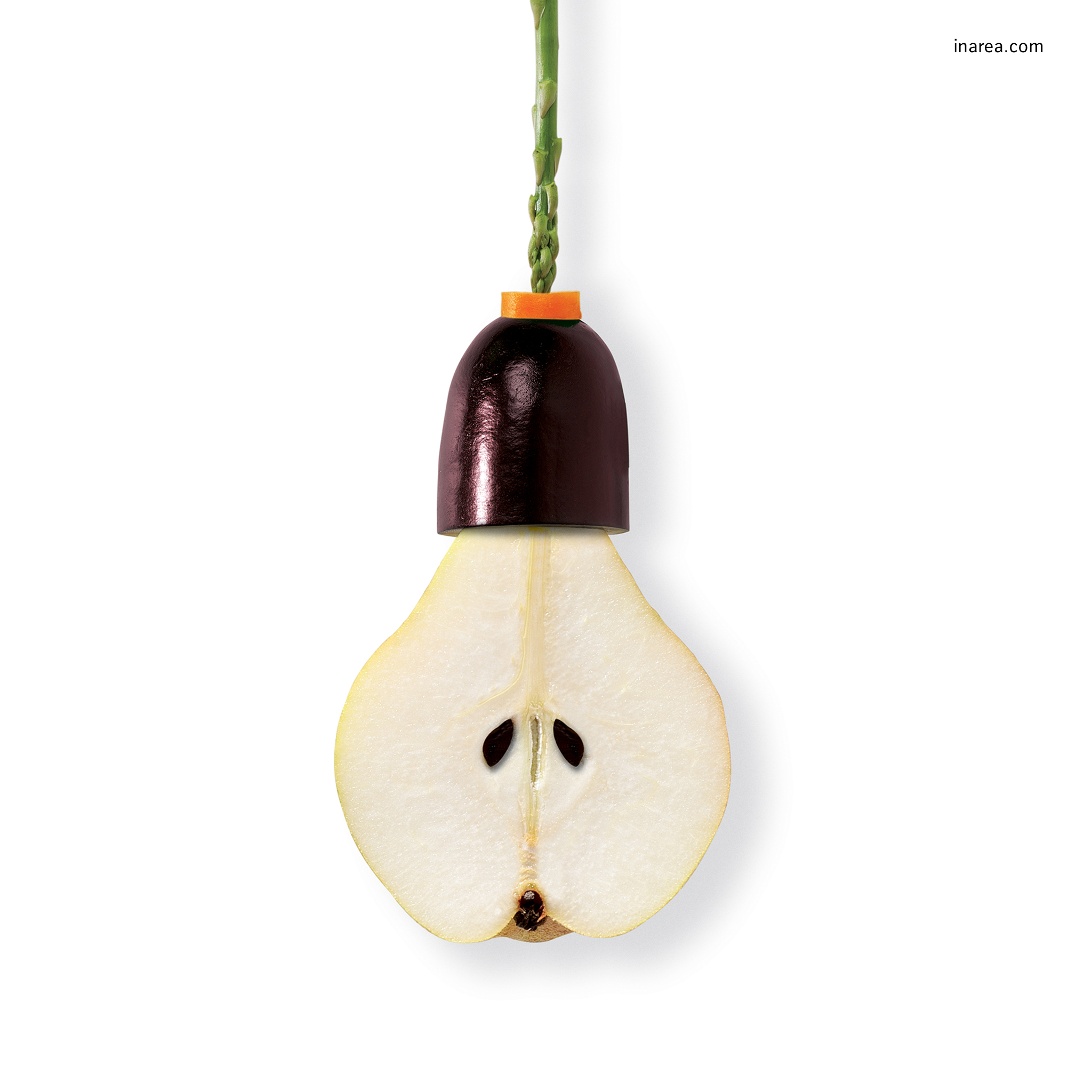

Newton’s apple – or was it a pear?

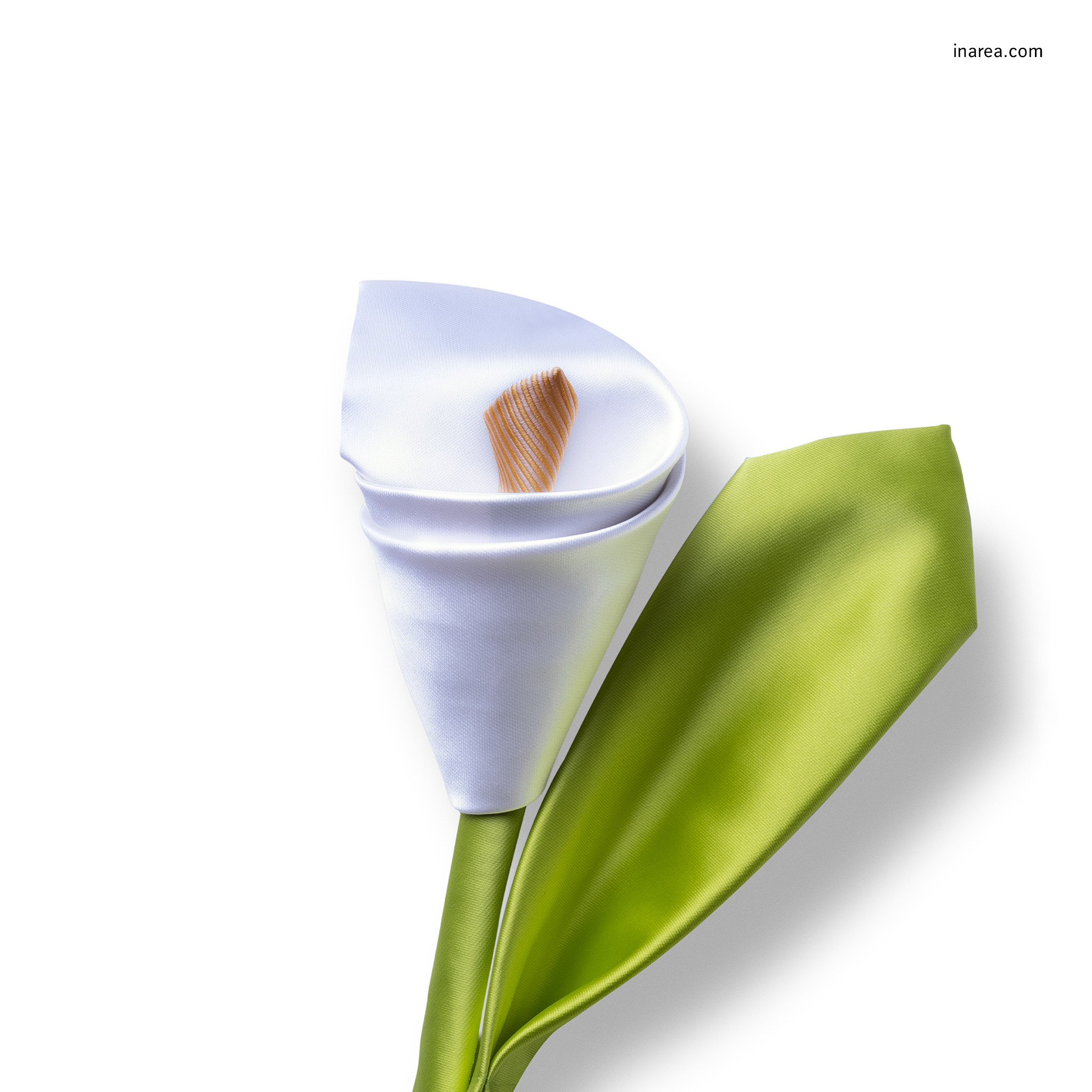

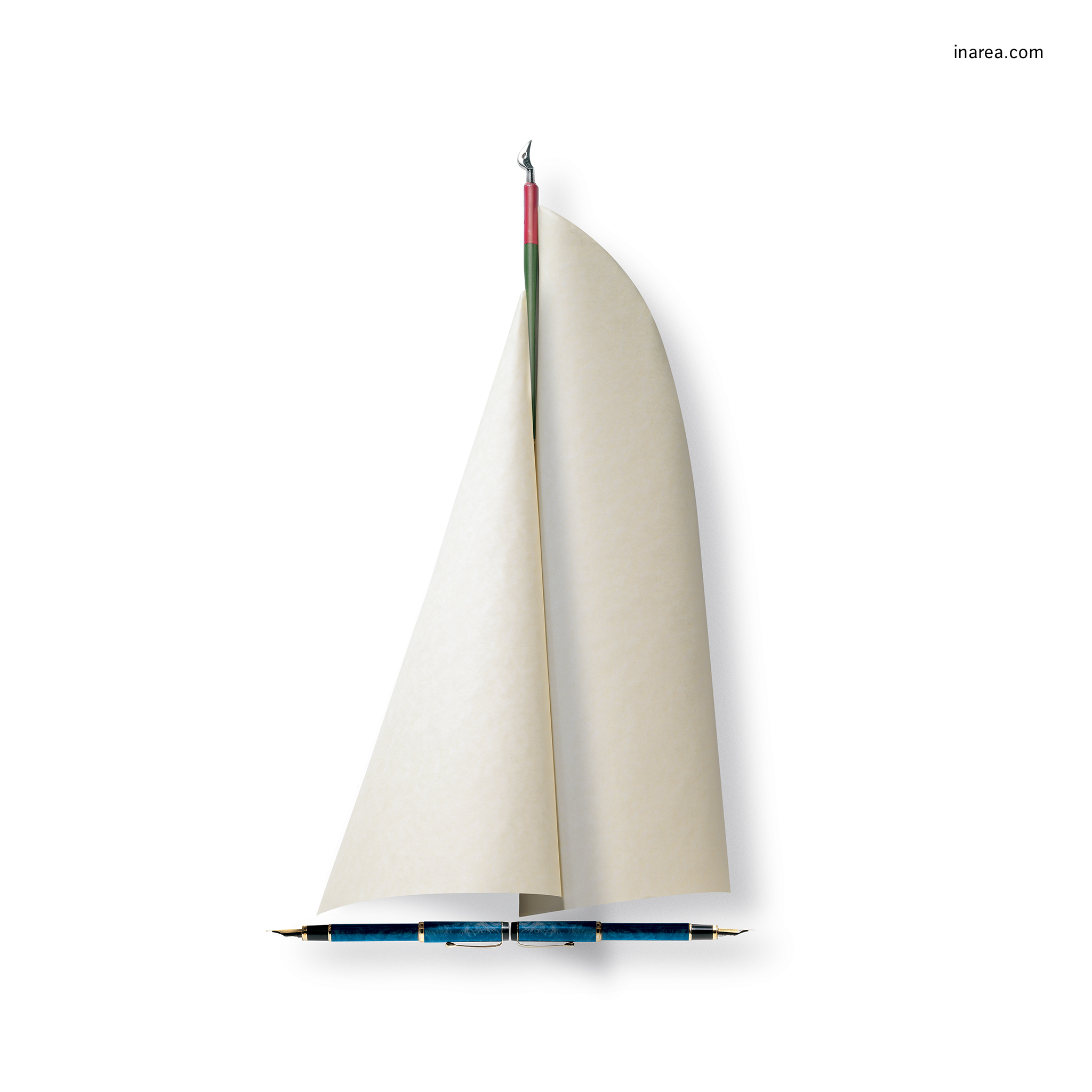

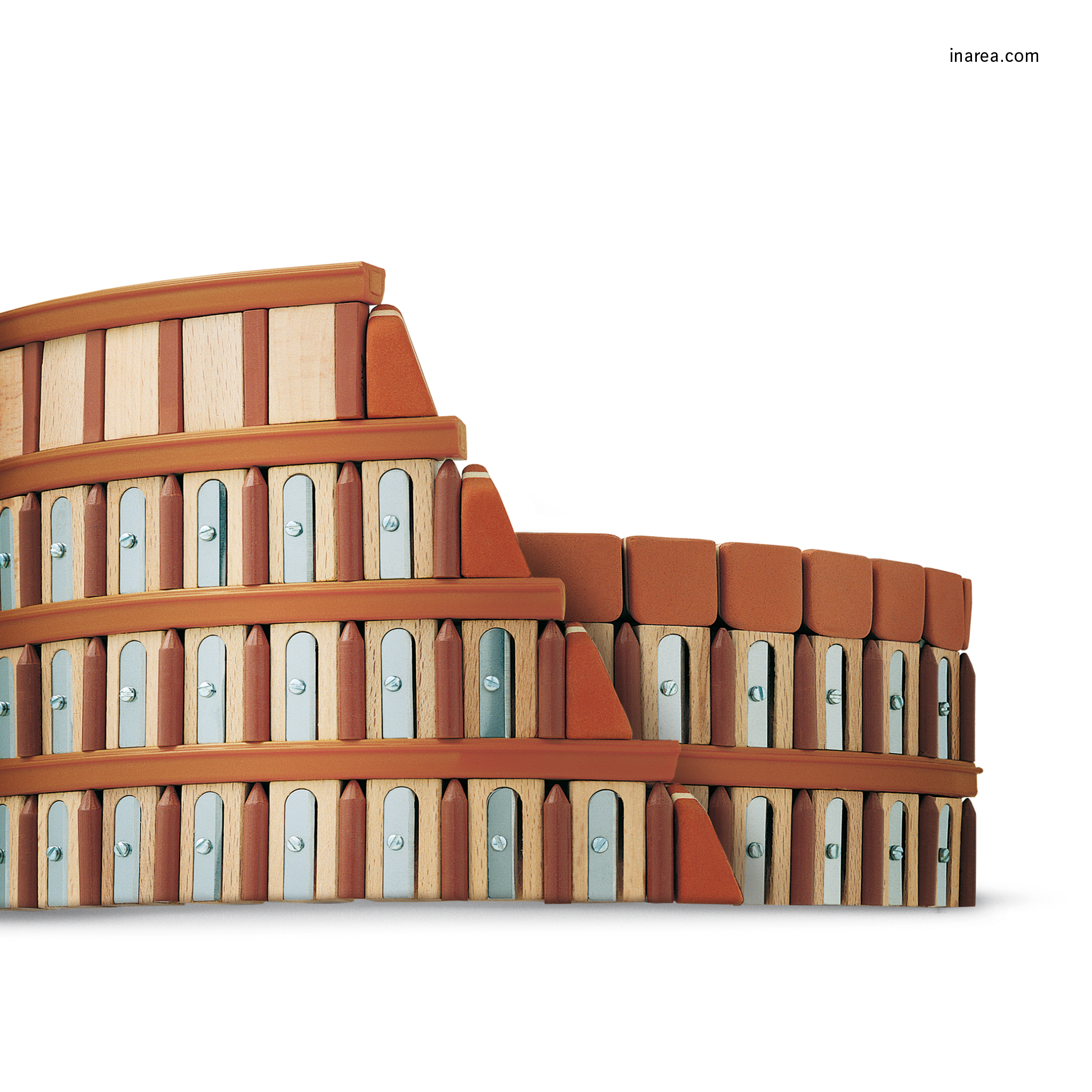

2022 is running along high-voltage cables, yet there was one writer who had no doubts whatsoever that this was going to be a dystopian year: the novel Fahrenheit 451 was written in 1953 and is set at an unspecified time after 2022, in a city which – despite being brightly lit up – is actually a very sad place to live in because the marching orders are to burn all books. Today both the Eiffel Tower and the Mole Antonelliana are having to turn their lights off early so as to save on electricity. Not even science fiction had gone quite so far… Come to think about it, everything our modern culture has accomplished, uninterruptedly since 1900 to date, is based on the glittering hustle and bustle of our cities as they rise higher and higher (see Boccioni’s painting “Città che sale”). Now it appears we are having to slow down a bit and even the world of design is changing accordingly. Nike, for example, is reducing the number of zips and seams on its sports clothes, the brand’s concept for the future being to streamline them more and more, thereby both simplifying its production cycle and cutting back on its energy consumption. Maybe, then, the fact that we have to decrease our volts at the present time isn’t such a bad thing after all: as falling apples (or should we say pears?) hit us on the head, they might indeed light up new ideas in there…