The vanishing point of a painting is the spot to which our eye is drawn and that gives us the intended perspective; but who’s to say the eye wouldn’t prefer to continue roving? A bit like Vermeer’s “Astronomer” which is now in the Louvre, but once belonged to the Rothschilds, the Jewish banking family. The Führer wanted to get his hands on it, so it was requisitioned in 1940 when the Germans took Paris, purportedly to rescue it from degenerate non-Aryan collectors. At the end of the war, the masterpiece was returned to France, but a small swastika is still stamped on the back.

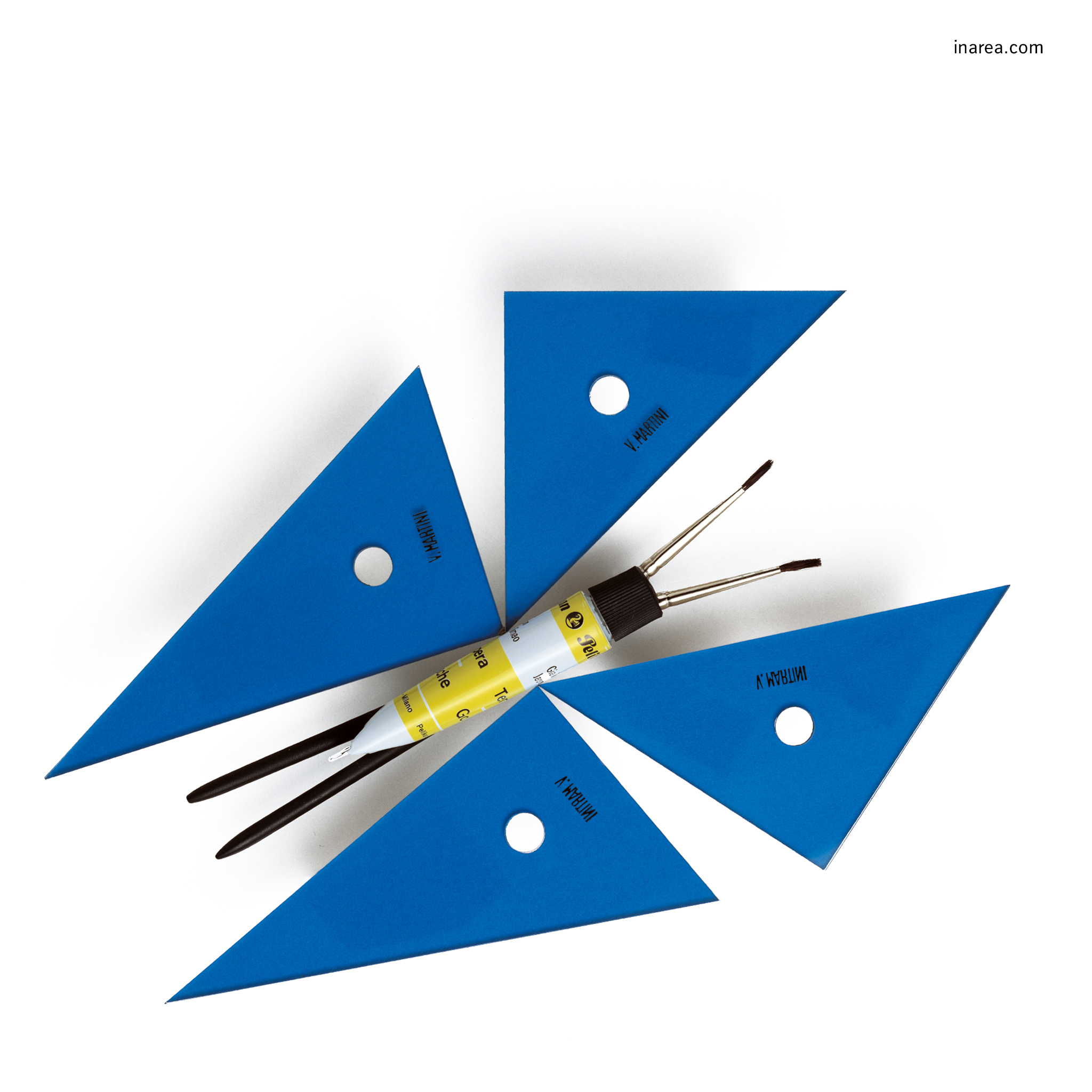

In more or less the same period, Italy was swarming with officials abusing their office: they would help themselves to works of art and escort them in their “Topolino” cars (the ancestors of the iconic FIAT 500) to provincial fortresses, where they were much safer from bombings; or they would keep a Piero della Francesca in their living room for a few days so as to make sure it stayed ‘at home’. This is what happened to the “Madonna of Senigallia”, the signature image of the “Liberated Art” exhibition (“Arte Liberata. 1937-47”) at the Scuderie del Quirinale (the former Papal Stables, now belonging to the Quirinal Presidential Palace in Rome). Visitors are invited to continue depackaging the poster we designed in the exhibition rooms, where they will find the entire epic of these “Monuments Men”. The exhibition is on until 10 April, but it seems spot-on to talk about it today to remind ourselves that memory is a matter of training: it begins every year on 28th January and continues until the 27th of the following year.

Piero’s Child is holding a flower and that is where we imagine our butterfly’s vanishing point to be. A stroke of the brush that deviates and goes back to the big picture, history, so that we can start not forgetting.